Wisdom from The Undoing Project

A Friendship That Changed Our Minds by Michael Lewis

Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is an absurd one. - Voltaire

Michael Lewis is a household name for many of us.

He’s written bestsellers such as Moneyball, The Big Short, and The Blind Side. I reviewed his book Flash Boys in a previous post.

He has a remarkable gift for describing people in extraordinary ways.

In The Undoing Project, Lewis tells the story of the genius duo (or, as he describes it, “the love affair but without the sex”) of Daniel (Danny) Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

These two psychologists sharpened each other’s thinking and often ended each other’s sentences.

Separately, they were geniuses; together, they changed the world.

The very world they impacted also drove a wedge between the two, leading to this beautiful relationship of minds to collapse.

Here are a few takeaways from the book.

The Beginning of Two Geniuses

Kahneman grew up in France as a Jew during the rise of Hitler.

As a boy, he saw Jews being exterminated, spent 4 years hiding in barns and chicken coops to evade capture, and saw his father die of diabetes.

Lewis describes what a young Kahneman was thinking at the time:

Danny wasn’t ready to abandon the idea that the universe had some unseen caring force in it. “I was sleeping under the same mosquito net as my parents,” he said. “They were in a big bed. I was in a small bed. I was nine. And I would pray to God. And the prayer was: I know you are very busy and that this is a tough time and all that. I don’t want to ask for much, but I want to ask for one more day.”

Later, after moving to Israel in 1947, Kahneman also witnessed the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

These experiences left him deeply curious about why people make the decisions they do, an idea that would guide his life’s work.

As an adult, Kahneman was reserved, doubtful, and often a loner.

Amos Tversky was the complete opposite.

He was outgoing, optimistic, and full of energy.

Raised in an academically focused household, he had the habit of doing only what interested him.

Lewis tells a story about Tversky going to a movie with his wife. Five minutes into the film, he decides it wasn’t worth watching, leaves the theatre, and picks his wife up afterwards.

Every moment of his life was spent on what he found intellectually stimulating.

Everyone who met Tversky thought he was the smartest person they had ever met.

However, when it came to human psychology, Danny had the ideas, but Amos knew how to communicate them.

They needed one another.

Together, they uncovered the hidden flaws in human judgment.

Human Bias

After Lewis wrote Moneyball (a story about how baseball scouts relied on gut instincts and flawed mental shortcuts, overlooking undervalued players), Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein reviewed the book.

They pointed out that what Lewis identified as “mental shortcuts” were biases that Kahneman and Tversky uncovered decades earlier.

Here are some of them:

Anchoring Bias

Anchoring happens when we rely too much on the first piece of information we encounter.

Let’s do an exercise.

Write down the last two digits of your cell phone number.

Ready?

Now, write down your best guess on the number of African countries in the United Nations.

Lewis writes:

People whose cell phone numbers were higher offered systematically higher estimates of African countries in the United Nations.

By the way, the answer is 54.

This shows how irrelevant numbers can influence our decisions, even when we think we’re being rational.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias is the belief that, after an event has happened “we knew it all along.”

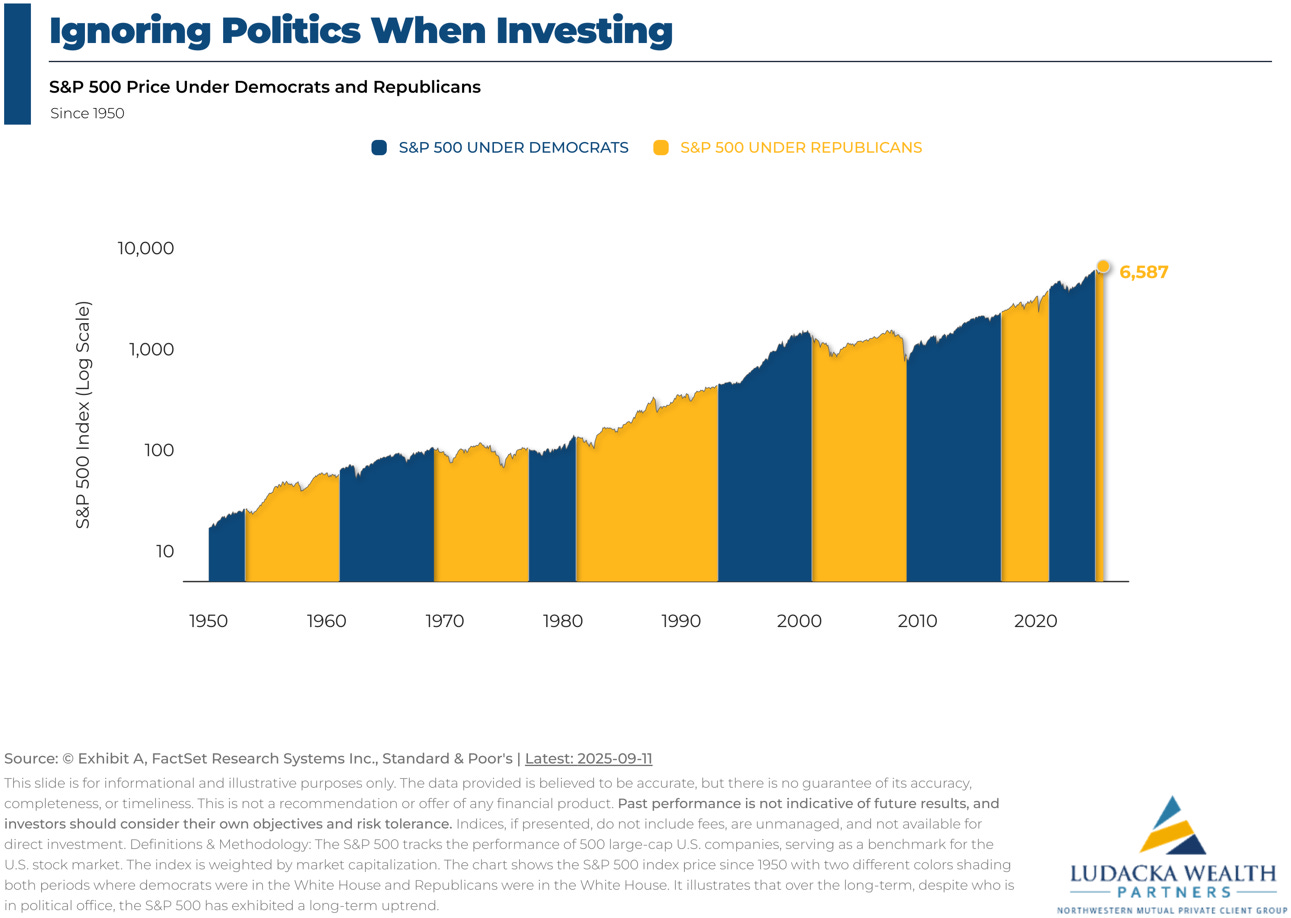

This happens all the time in the stock market.

After elections, you’ll hear some people say they “knew” the stock market would fall because the opposing candidate was elected.

They didn’t.

The stock market has continued to move higher regardless of party affiliation.

Warren Buffett once said:

In the business world, the rearview mirror is always clearer than the windshield.

That’s hindsight bias – the illusion of certainty only after an outcome is already known.

Loss Aversion

Kahneman and Tversky found that people feel the pain of losses about twice as strongly as the pleasure of the same amount of gains. Losing $100 hurts more than winning $100 feels good.

In investing, this leads to common mistakes.

People hold losing stocks too long, hoping to get back to even, while they sell winning stocks too soon, fearing their gains will disappear.

The losers drag on performance while the winners are cut short.

Loss aversion explains why markets are often driven by fear.

Final Thoughts

Lewis spent a lot of time with Danny getting research for the book, but he could only recreate Tversky through the memories of those he influenced. Tversky passed away in 1996.

Lewis said that Tversky was very much alive because of his impact on so many.

He joked that he was the B student writing about the A students.

I thought it was an A+ book.

If you’re tired of reading boring psychology papers, but like psychology, this is the book for you.

Give it a read when you can.

Keep learning. Keep growing. Keep going.

Now here’s what I’ve been reading, listening, and watching:

Yeager: An Autobiography by General Chuck Yeager on Founders podcast

Alfred Nobel: A Biography by Kenne Fant on Founders podcast

Playing Your Own Game on The Morgan Housel podcast

The 5 Types of Wealth by Sahil Bloom

Children’s book (I have a 6-year old): One Vote, Two Votes, I Vote, You Vote by Bonnie Worth

Here’s what I’ve been writing: