Private Markets: Coming Soon to a Portfolio Near You

Once upon a time, going public was the ultimate badge of honor for founders.

They couldn’t wait to ring the bell at the NYSE or Nasdaq to raise capital and scale fast.

For example: Amazon went public in 1997, when it was three years old. Google's IPO (initial public offering) was in 2004, when it was six years old.

Times have changed.

For example: Two of the world’s best-known companies, SpaceX (which is 23 years old) and OpenAI (9 years old), are still private, with plenty of eager investors lining up at the door.

Despite more money sloshing around than ever before, fewer companies are going public.

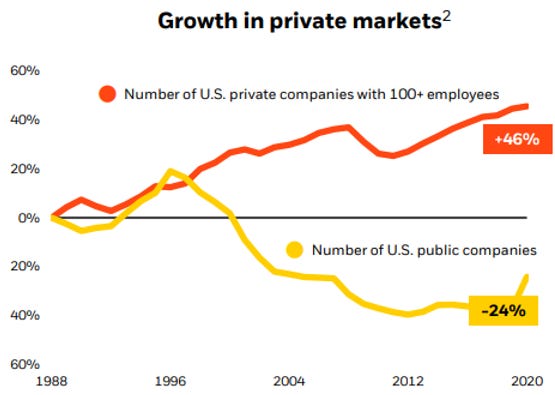

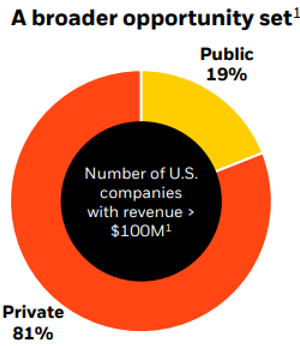

The chart below shows that since 1988, the growth of private companies has been 50%, while the number of companies going public during the same time period has fallen by a quarter.

Of the companies generating over $100 million in revenue, 81% are private companies.

Why do they stay private?

Two big reasons stand out:

Capital is Abundant and Typically Patient

Thanks to the explosion of venture capital, private equity, family offices, and institutional investors, companies no longer need to IPO to keep the lights on or scale their operations, and many of their investors are willing to wait.

Less Red Tape

With less regulatory red tape, fewer disclosure requirements, and more operational control, many founders and boards see no urgency in going public.

Why the Boom in Private Markets?

Compared to public markets, private markets are still tiny.

Apollo’s Chief Economist, Torsten Slok, notes that global bonds (i.e., fixed income) and global stocks (i.e., equity) easily top the $100 trillion mark.

As of the first quarter of 2024, global private capital is just $14.5 trillion.

Some of the biggest names in the finance industry want that to change.

BlackRock is expanding its private markets division. From private infrastructure to private credit, they’re pushing hard to offer products that suit institutions and affluent individuals.

They’re even planning to add private equity and private credit to their target-date funds in the first half of 20263.

State Street is doing the same thing.

Vanguard, historically slower to adapt to new investments, has been building partnerships to catch up.

These giants are driving down costs and friction and see private markets as the future.

What’s The Catch?

Private investments usually cost more than a plain-vanilla index fund.

Many charge a management fee plus an incentive fee. For example, they could charge 2% of an investor’s assets and 20% of profits above a certain return.

Some justify the higher fees by pointing to their expertise in finding great opportunities and track record.

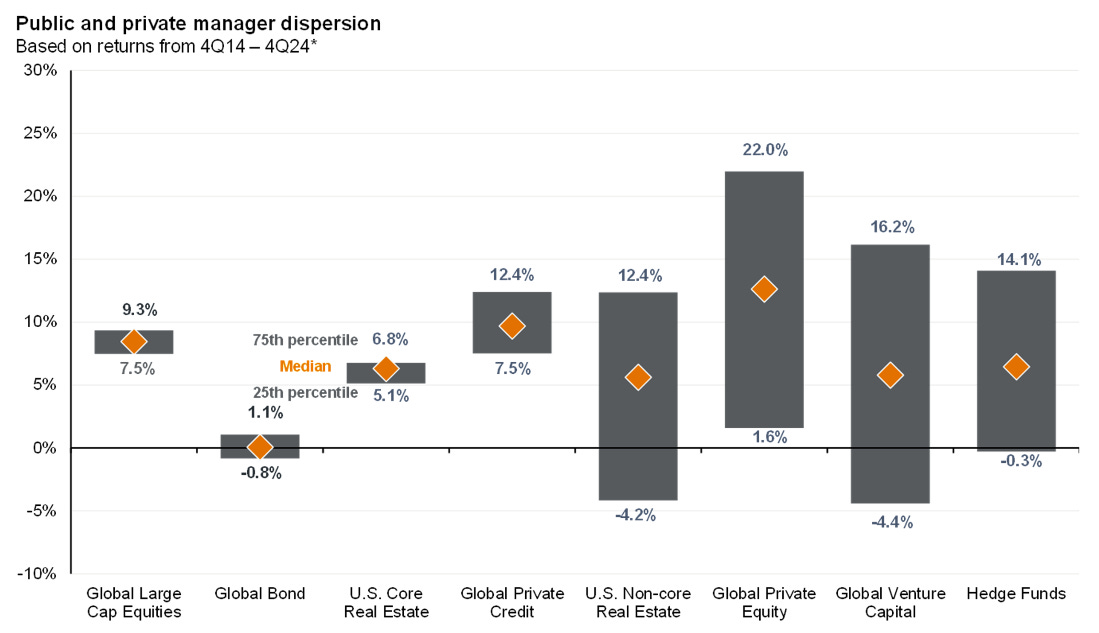

There is merit to that argument, but finding a great manager is critical.

This great chart from JP Morgan’s Guide to the Markets deck shows that there are many bad managers, especially in the private equity, venture capital, and hedge fund world.

For example, between 2014 and 2024, the difference between the best and worst private equity managers was 20% per year.

Another thing to know: private markets are illiquid, meaning you can’t cash out whenever you want.

This could be good or bad, depending on who you are.

It’s risky if you need cash within the next 5 years.

However, illiquidity can help investors stay patient.

The late great Charlie Munger said:

Waiting helps you as an investor, and a lot of people just can't stand to wait. If you didn't get the deferred-gratification gene, you've got to work very hard to overcome that.

The structure of these private investments enforces patience.

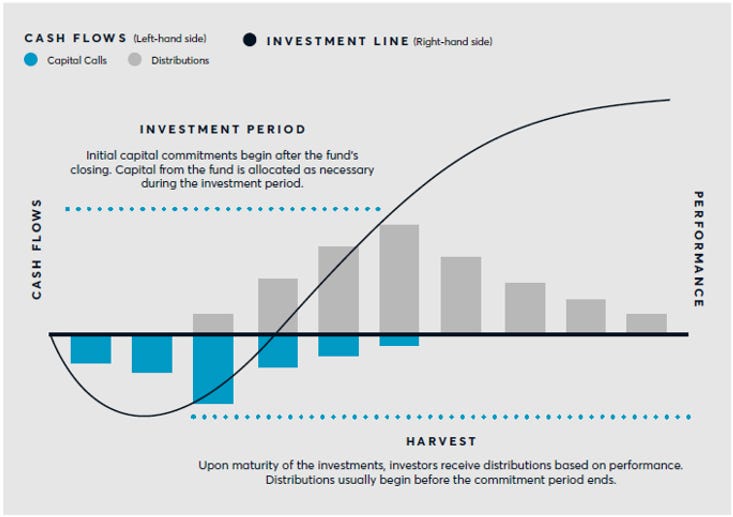

Many private investments are structured in drawdown funds.

This is the traditional private equity format, in which an investor commits a sum of money to a private strategy, and the manager “calls” that capital over time, deploying it as deals come along.

The illustration below by CAIS IQ and Mercer shows how this works.

Blue bars mean investors put money in the drawdown fund, and returns (i.e. grey bars) are usually distributed years later.

This process could take years, and an investor’s cash is locked up.

Some newer structures, like an interval fund, allow for quarterly redemptions (i.e., withdrawals).

Investors can generally buy in anytime but are capped on how much they can take out (usually 5% of the fund’s assets).

Those limits may be reached quickly in stressed markets, leaving some investors stuck waiting.

That’s not necessarily bad (i.e., forced patience can be a virtue), but it’s the reality investors need to understand.

Final Thoughts

Private markets aren’t for everyone.

They require a long-term mindset and an understanding of liquidity tradeoffs.

Those willing to thoughtfully venture into private markets can receive diversification, differentiated returns, and access to a broader slice of economic growth.

Just be sure to match your cash flows with your portfolio’s liquidity.

The traditional 60% stock and 40% bond portfolio isn’t dead, but it might be getting some new neighbors.

The End

Keep learning. Keep growing. Keep going.

3: Source: Wall Street Journal. Anne Tergesen. June 26, 2025. Blackrock Deepens Push Into Private Investments for the Masses.

Now here’s what I’ve been reading, listening, and watching:

Ernest Shackleton (the man who kept his 27 man crew alive for nearly two years in Antarctica) on Founders

Just Keep Buying by Nick Maggiulli

The Seven Frequencies of Communication by Erwin Raphael McManus

The 5 Types of Wealth by Sahil Bloom

Children’s book (I have a 5-year old): If I Were President by Catherine Stier

Here’s what I’ve been writing: